It is widely understood that businesses need a vision, a mission, or a purpose—some guiding principle or North Star that shapes their direction and motivates their people. Whether referred to as a mission statement, a vision, or a purpose, the concept serves as a compass intended to align organizations toward meaningful impact.

Most leadership teams acknowledge the importance of this concept. Yet, when we examine how purpose actually functions within organizations, a consistent gap emerges between what is stated and what is lived. While leaders speak of purpose with conviction, they often struggle to embed it in their organizational culture and daily decision-making.

If leaders already know the importance of purpose, why is it that so many leadership teams fail to operationalize it?

Drawing from research, leadership interviews, and the example of Patagonia’s recent purpose transformation, we will examine the barriers that prevent purpose from becoming practice and why leaders often default to the seemingly safer path of being “practical.”

Two Common Approaches to Purpose in Business

In our experience working with organizations across industries, we observe two prevalent approaches to purpose:

1. The “Purpose is Fluff” Camp

The first approach belongs to organizations that disregard purpose as unnecessary or irrelevant. Leaders in these businesses tend to operate with a pragmatic focus on efficiency, profitability, and execution, often dismissing purpose as a distraction from the “real work” of running the business.

For example, leaders of a plastic cup manufacturing company or a grocery store might say:

“We don’t have a purpose that saves the world. We just want to earn a living and do the best we can.”

This perspective is not necessarily flawed. In these organizations, the strategy and operations align with their stated intent: to survive, serve customers, and make a profit. There is coherence between their business model and their stated priorities. For them, “purpose” often translates to maintaining operations and providing stable employment.

From an ontological perspective, however, it can be argued that no business is inherently devoid of purpose. A company may not have unearthed or articulated an inspiring purpose, but this does not mean it does not exist. Every business has an impact—whether acknowledged or not—and understanding this impact can be the first step toward meaningful transformation.

This deeper exploration lies beyond the scope of this article. For today’s purposes, we will focus on the second camp—organizations that actively seek to define and align around a stated purpose, yet often struggle to operationalize it.

2. The “Purpose-Driven, But Stuck” Camp

The second approach involves organizations that attempt to define and align around a purpose. They may be inspired by a leader’s personal vision or the collective ambition of the executive team. Many such organizations invest significant resources to craft a compelling purpose statement, sometimes partnering with consultants or branding experts to sharpen the message and ensure external consistency.

At first glance, these organizations appear to be purpose-driven. However, in many cases—even among financially successful businesses—there remains a significant disconnect between the leaders’ stated purpose and the lived experience of employees.

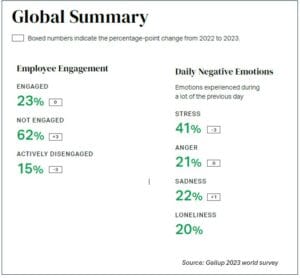

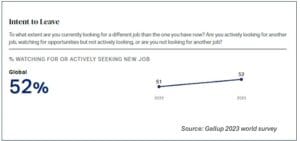

The Gallup 2023 global workplace survey, based on data from 128,000 employees worldwide, reveals that 77% of the global workforce is disengaged. In Europe, the figure is even lower. Executives and managers are not immune; they, too, are employees, and their disengagement impacts their ability to lead effectively. Many leaders push themselves forward despite this misalignment—often resorting to white-knuckling their way through initiatives without a deep connection to the purpose they promote.

This raises a critical question:

If leaders understand the need for purpose, why does it so often remain an idea rather than a lived experience?

To answer this, we must examine two ontological pillars:

- The way of being of the leader and their personal connection to purpose.

- How purpose shows up in the day-to-day operations of the organization.

What Does It Mean to Operationalize Purpose?

In an ontological business context, operationalizing purpose is not simply about aligning strategies or implementing new processes—it is fundamentally about who the organization is being. Purpose moves from being an abstract concept or a carefully crafted statement into something that is embodied through the daily actions, decisions, and conversations of leaders and employees. An organization’s way of being—its culture, leadership presence, and relational dynamics—must reflect its declared purpose. It shows up not only in what the company does but in how it does it: in the quality of its relationships with stakeholders, in the integrity of its decision-making, and in the authenticity with which it engages the world around it.

For example, I recently worked with a family-owned manufacturing company that had articulated a purpose centered on “enhancing well-being through sustainable products.” Initially, the purpose served as an inspiring message for branding and customer communications. However, when faced with a critical supply chain decision—choosing between a cheaper, less sustainable material versus a more expensive but environmentally responsible option—the leadership team was tested. There was real concern about profit margins, shareholder expectations, and competitive pricing. After deep reflection and alignment conversations, the team chose to honor their stand. They opted for the sustainable material, even though it meant short-term financial sacrifice. Over time, this decision reinforced their credibility with both customers and employees, building a culture of trust and pride. Employees began to take ownership of the purpose, suggesting new sustainability initiatives that went beyond the leadership team’s original plans. The organization’s way of being shifted—from simply declaring a purpose to collectively living it.

Ultimately, operationalizing purpose in an ontological business context means that purpose is no longer an external mandate that people comply with, but an internal commitment that individuals and the collective own and embody, shaping every aspect of the organization’s way of being and doing.

Why Purpose Efforts Fail: Two Critical Factors

1. The Disconnect Between Leaders and Their Own Personal Purpose

In the past several years, I have conducted hundreds of interviews with senior executives, future CEOs, and MBA students from leading institutions, including Harvard, Yale, and IESE. Two patterns consistently emerge:

These leaders are remarkably talented and intellectually capable. They possess extensive track records of success across industries and geographies.

Despite their success, many lack clarity around their personal “why.” They often cannot clearly articulate who they want to impact, what contribution they aim to make in the world, or the stand they are taking as leaders.

This lack of personal clarity creates a profound challenge. When these individuals ascend to positions of organizational leadership, they are expected to provide direction and clarity for the business, yet they themselves have not resolved their own purpose. The result is often an overreliance on intellectual frameworks and external advisors to craft a company purpose—one that may resonate superficially but lacks deep, personal connection.

While these leaders are typically driven and ambitious enough to push through the discomfort, they may unconsciously create purpose statements that are inspiring on paper but disconnected from lived experience.

2. Purpose is Not a One-Time Task—It’s an Ongoing Process

Even when a leader succeeds in defining an authentic organizational purpose, they often fail to sustain and operationalize it. Purpose is not a static declaration. It is a dynamic conversation that requires constant engagement, refinement, and embodiment.

Purpose must show up in:

- Strategic decisions

- Organizational structures

- Hiring practices

- Performance evaluations

- Customer relationships

- Internal conversations and culture

This is where many organizations lose the thread. Purpose becomes something leaders discuss during annual retreats or board meetings. Day to day, however, they default to operational tasks and strategy execution—the areas where they feel more competent and in control. They actually often start pretty well but then they just stop. Purpose becomes overwhelming and uncomfortable. What´s a better escape than talking about strategy and looking smart.

Operationalizing purpose, from an ontological perspective, is an ongoing commitment to living in alignment with the stand the organization has chosen to take in the world. It is not a fixed endpoint or a project with measurable KPIs alone. Rather, it is a dynamic process of continuous reflection, realignment, and practice, especially in moments of uncertainty, conflict, or complexity. Leaders must consistently examine whether they—and their teams—are showing up in ways that embody their declared purpose. This requires courage, as it often means making difficult decisions: walking away from profitable opportunities that compromise the organization’s stand or engaging in uncomfortable conversations to restore integrity within the team.

Patagonia: What It Took to Operationalize Purpose

Patagonia offers a powerful example of the work involved in operationalizing purpose.

At the Harvard Families in Business Conference, Charles Conn, Chairman of Patagonia, described their decision in 2022 to shift the company’s purpose from:

“Cause no unnecessary harm” to

“We’re in business to save our home planet.”

This bold statement required more than a branding exercise. Conn explained that it took two years to embed this new purpose into the fabric of the organization.

- They engaged in difficult conversations with stakeholders and investors.

- They revised their supply chain, product lines, and strategic priorities.

- They aligned organizational culture and operational processes with their commitment.

As Conn stated:

“We didn’t know how to do it. It involved tough conversations with stakeholders, investors, and within the team.” Charles Conn, Chairman of Patagonia

This is what operationalizing purpose looks like: not a weekend retreat, but a long-term, high-stakes endeavor requiring courage and resilience.

Why Leaders Default to “Let’s Just Be Practical”

If we as business leaders like the idea of purpose, but who have never truly been connected to our personal purpose and are not truly ready to face the discomfort of going throw the messy process of purpose discovery and ¨looking bad or stupid¨ on the way, we will never operationalize our purpose. It is much easier to say in the the process “let’s be practical” and focus on the strategy. It will make us look smarter and make us seem that we are making stuff happen. However, it will never create an environment of true loyalty, creativity and innovation. Hence, when faced with the complexities and uncertainties of operationalizing purpose, many leaders default to the familiar comfort of strategy and operations. The phrase “let’s just be practical” often signals a retreat into more measurable and predictable territory.

This is understandable. Strategy offers clarity, metrics, and short-term validation. It satisfies shareholder demands and delivers tangible results. Purpose work, by contrast, is messy, ambiguous, and difficult to measure in quarterly reports.

But this retreat comes at a cost:

- Employee disengagement

- Erosion of trust

- Loss of innovative potential

- A culture that defaults to compliance rather than commitment

Purpose cannot be operationalized through strategy alone. It requires leaders to stay in the discomfort of ambiguity, to navigate difficult conversations, and to make decisions that may not please everyone.

The Courage to Stay the Course

Technically, we might say there is a third camp: organizations that have chosen to do the ongoing work of operationalizing purpose. Patagonia is one such example. These organizations do not merely define purpose; they live it through every decision and action they take.

However, you do not need to be Patagonia to do this work. You do not need global recognition, massive resources, or a revolutionary product.

All you need is a stand. The reality is that when you take a stand—whether it’s for the planet, for health, for ending addiction, or even for putting a smile on people’s faces through ice cream—you need to be prepared to have the courage not to give up on that stand.

This means giving up your need to please the people around you. And that’s hard. We are wired to want others to like us, to seek approval and acceptance. But a strong purpose will inspire some people, and it will also turn others away. Some employees will be fully on board. Others won’t. Some will become more loyal. Others will leave. Your business partner may leave. Another one may join…or not. Staying true to your purpose is a risky game and we need to have the courage to stick with it. These are difficult, ongoing conversations that need to be held inside an unwavering commitment to what you stand for. It also requires trust that things will turn out because it is risky.

Operationalizing purpose requires deep self-reflection, consistency, and resilience. It demands choosing a stand, committing to it, and continuously refining it—even when it feels uncertain or uncomfortable.

Most importantly, it requires the courage to resist the easy path of “let’s just be practical.”

P.S. If this resonates, subscribe below (the box at the very bottom on the right) for more on ontological leadership and relationship transformation at your family business, start-up or enterprise.